How does one measure the depth of civic engagement in a particular city? What metrics can we use to register the strength of conscience? How can the soul of the city be indexed?

How does one measure the depth of civic engagement in a particular city? What metrics can we use to register the strength of conscience? How can the soul of the city be indexed?BOTC has written before about the simple care of the city. By “simple care” we mean the neighborly awareness and recognition of other urban dwellers or users. The exhibition of simple care is most apparent during the winter when some landlords or owners make little or no attempt at removing snow and ice from city sidewalks. No snow removal reflects an obvious disregard or de-valuing of the city. Hence, snow removal is a simple metric of civic engagement.

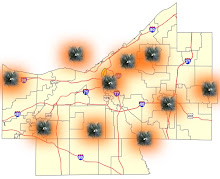

Another more ritualized metric that can be utilized is the community parade. BOTC has always been interested in the community parade—not necessarily at the scale of Cleveland’s Saint Patrick’s Day Parade, but more on the scale of the community Memorial Day Parade. BOTC has documented several local Memorial Day parades and ceremonies over the years, including events in Bedford, Chagrin Falls, Parma Heights, and Parma.

The Memorial Day Parade, an American ritual that has its roots in the Civil War, is, if closely examined and witnessed, a poignant and touching exhibition of civic engagement and patriotism. Although the routines stay the same every years, the gathering of veterans’ groups, high school bands, boy and girl scouts, police and fire departments, assures the solemnity and importance of the annual procession. The young and the old march together, maintaining the generational passage of the sacred tradition of honoring the fallen. The grizzled veteran straightens at the playing of the National Anthem or weeps at the emotion of Taps, all in public view and in participation with others who have not served. Children hold little American flags and fidget during moments of respectful silence, beginning to understand the rituals that they will perform in later decades. They all honor citizens who sacrificed.

However, what happens if no one comes to the parade? What if very little people actually spend a half-hour of their holiday participating in—just merely watching, mind you--the Memorial Day Parade? This is what occurred in Parma yesterday. Parma is a city of, according to the US Census Bureau, around 80,000 people. Approximately 9,300 veterans live in the city, or about 14% of Parma’s population, more than average American city. Many houses fly Marine Corps and Navy flags. Blue Star Flags hang in many windows. Yet, how can so little people turn out for such a solemn occasion?

This lack of visible and tangible participation in one of the civic days of obligation is quite distressing. This is, in our estimation, a metric that portends negatively for the soul of the city, our city. Once an urbanism or suburbanism loses its pride and erodes into apathy, the core begins to rot and weakens, eventually withering away.

BOTC hopes what we witnessed is merely an anomaly.